- supergoods

- Posts

- Why one guy owns your brand's past

Why one guy owns your brand's past

Vintage packaging collecting with Jason Liebig

Food and beverage packaging is mostly just trash. Quite literally - for most people, it’s something they simply throw away.

For us food & bev marketing nerds, it’s a sales tool and brand building asset.

To Jason Liebig, it’s neither of those things. It’s treasure.

One of my favourite industry conversations last year was with Jason in a New York diner on a freezing cold winter day. We sat for hours discussing the history of brands and packaging in a much deeper sense.

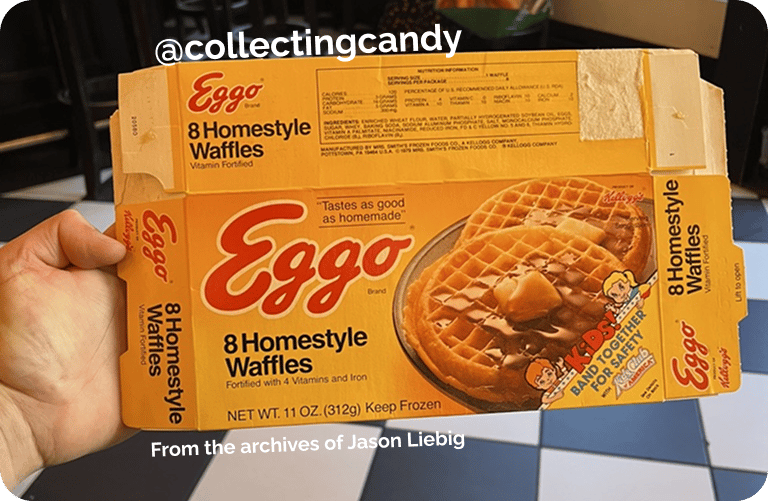

Jason owns one of the most comprehensive consumer packaging archives in the world. Tens of thousands of packs, wrappers and boxes. He’s a regular expert on TV shows like The Food That Built America and he regularly consults on period-specific TV programs like Stranger Things and Mad Men.

What struck me about our conversation wasn’t just the cool nostalgia element of historic packaging, but what Jason’s work exposes.

Packaging is more than just design. Over time, it becomes how culture remembers products. And the most shocking part is how careless brands are with that memory.

This edition of supergoods is proudly brought to you by Stickybeak

I’m teaming up with the legends at Stickybeak to talk about my favourite topic: packaging effectiveness.

This is not a webinar you half-listen to in the background while demolishing an overpriced bánh mì and pretending it counts as a lunch break.

You’ll want to actually pay attention.

We’ll cover:

Practical frameworks for effective packaging design

How to think about distinctiveness (without the fluffy brand waffle)

What to validate with consumers — and when it’s actually worth doing

Normally, I charge a lot of money for this.

But we’re doing something a bit silly and giving it all away for free.

Hit the link for dates and details.

Packaging as a memory-device

We usually talk about packaging as persuasion. Shelf impact. Claims. Colour. Cut-through.

But stretch the timeline out far enough and packaging changes roles. It stops behaving like advertising and starts behaving like infrastructure for building memories.

Jason described it clearly:

“At a certain point, packaging stops selling and starts storing information.”

Logos, colour systems, mascots, formats - these aren’t just aesthetic choices. They’re memory devices. Ways the brain stores and retrieves brands over decades. They allow recognition to survive long gaps, category drift, reformulation, even ownership changes.

When organisations pay attention to the past and preserve the history, brands can build their assets and memory structures for the long term.

Stranger Things fans will recognise this - straight from Jason’s archives. Credit to Jason Liebig for bringing this along for our chat.

But after speaking to Jason, it’s surprising how much history gets dumped in the garbage.

Most brand history isn’t lost, it’s discarded

One of the more uncomfortable themes from our conversation was how often brand history is lost not through malice, but indifference.

Offices move. Warehouses get cleared. Storage budgets get cut. Boxes are thrown out because no one can clearly articulate why they matter.

Jason has seen this firsthand:

“Entire corporate archives get dumped because someone asks, ‘Why are we paying to store this?’ and no one has a good answer.”

Entire decades of packaging end up in skips.

Before they were rebranded “Starburst”. Original packaging from Jason

In many cases, the only reason that material survives is because someone pauses - an intern or a cleaner stops to think it might be worth something. And that’s when people like Jason get phone calls - with pallets of brand history ready for the dump.

The irony is sharp: the companies with the deepest brand equity are often the worst stewards of their own memory.

When collecting becomes custodianship

So what does the life of an avid vintage packaging collector look like? Jason compulsively checks eBay, searching for the elusive missing piece. He spends time sorting, scanning and filing his archives to preserve and protect them.

But mostly, it’s just a hobby. Only about 10% of Jason’s archive is available to view online. His philosophy is to only share stuff that doesn’t already exist on the internet.

Jason didn’t build his archive to glorify the past. He built it because much of it wasn’t documented anywhere else.

Over time, the scale changed the responsibility.

“I don’t really own it anymore. It owns me.”

That line stuck. Because it reframes the work. This isn’t nostalgia content. It’s cultural maintenance.

Once you realise entire decades of packaging and brand history only survived because one person bothered to care, the stakes change.

The very first Rolo wrap from 1937 - unmistakably Rolo. Fkn cool!

One of my favourite topics was simply discussing how little these mega brands have actually changed over time. That consistency is so powerful for building long term recognition and strong brand value through memory structures in mass audiences.

Old pack designs hit different

When you study older packs closely, a pattern emerges.

Packaging was built to survive constraint. Poor printing. Partial visibility. Chaotic shelves. Time.

Jason learned this before FMCG, working in comics. A comic cover is packaging. You rarely see it in full. It has to work cropped, stacked, half-hidden.

That pressure forces discipline: hierarchy, contrast, restraint.

Once you see that discipline in older packaging, it becomes obvious how intentional it was - and how rare it is now.

History reveals what actually endured

This is the real value of archives - not aesthetics, but evidence.

When brands lose their packaging history, they don’t just lose nostalgia. They lose reference. Paying attention to what worked in the past, how brands looked, how they communicated, what made them successful is so critical to preserving the value of brands.

Archives show which elements stayed consistent, which flexed, and which disappeared entirely. They show how brands adapted without losing recognisability.

Without that material, teams are left guessing - often confidently, but blindly.

Packaging is the most persistent media a brand owns

We often say packaging is “free media”.

That undersells it.

Packaging is the most persistent media a brand owns. It lives in kitchens, cupboards, fridges, pantries. It’s handled, not just seen. Repeatedly. Over years.

Campaigns end. Packaging accumulates memory.

Which makes throwing it away - physically or strategically - one of the most tragic ways brands erase themselves.

The value of history

Jason’s archive isn’t important because it’s large. It’s important because it captures what brands failed to keep.

It documents how culture actually encountered products - not how companies wished they were seen.

Packaging isn’t just how brands speak to consumers in the moment.

It’s how they’re remembered long after.

Thank you to Jason for our chat. He regularly consults with brands, does talks on packaging history and probably knows more about your brand than you do. Reach out to him and follow him online.

What did you think of today's story?Click to vote, it helps us improve. |

Reply